A Russian revolutionary in the Slocan Valley

- Greg Nesteroff

- Dec 22, 2018

- 8 min read

Updated: Jun 3, 2019

Twice this year I’ve learned secret details about someone that made me re-evaluate everything I thought I knew about them.

The first case concerned pioneer prospector Eli Carpenter, who co-discovered the claim that started the Silvery Slocan mining rush and once walked a tightrope over Slocan City’s Main Street.

Although it was rumoured Carpenter came to BC after his wife was unfaithful, I was dismayed to discover he tried to kill her and her paramour. His drunken stupor prevented him from carrying it out.

The latest case concerns Konstantine (or Constantine) Popoff, pictured below in an undated but early 1900s photo from the Slocan Valley Historical Society, 2013-01-3089. His wife Emilie was acclaimed as mayor of Slocan in 1946 — the first woman in the Kootenays to hold such a position. Although they left the area a few years later, their name remains associated with their former farm, which became a Japanese Canadian internment camp during World War II.

Konstantine’s surname was originally Пирожко, transliterated as Pirozhko, although often spelled Piroshko or Piroshco. I never read too much into this. I thought he probably changed his name around the time he moved to Canada from Russia. Popoff was easier to spell and pronounce, perhaps, and it likely didn’t hurt that it was a common Doukhobor surname.

The Popoffs were not Doukhobors but their move to West Kootenay might well have been influenced by the Doukhobor migration from Saskatchewan to BC in 1908.

In 1969, Emilie wrote a brief autobiography which stated: “Whilst in Odessa, we read about Canada and felt a great incentive to go there. In the early part of January 1905, my husband-to-be and I arrived in New York. Shortly afterward, Mr. Popoff left for Canada.”

Although I’ve been collecting information on the Popoffs for close to 20 years (and might one day get around to publishing a full biography of them), the first real hint that Emilie omitted many key details only emerged recently when the entire run of The Vancouver Sun was made available through newspapers.com.

Konstantine was a partner in a Nelson real estate firm and his ability to speak Russian led to him act as agent and interpreter for Doukhobor leader Peter (Lordly) Verigin. This relationship continued even after Konstantine’s father Jacob accused Verigin of assault in 1912. The case was dismissed, with Jacob ordered to pay Verigin’s costs.

However, Konstantine also ended up in court against Verigin in 1917. Verigin filed a claim for $2,000, an alleged secret commission on the purchase of a 1,500-acre ranch near Lundbreck, Alta., intended for a new settlement. According to an item in the Sun of Nov. 25, 1917 (seen below), Verigin “was awarded the $2,000 and a further sum of $5,000 on the ground that Popoff, his agent, had encouraged the vendor to hold up his price and that but for that encouragement it would have been purchased for much less than the $64,000 involved.”

The court of appeal reversed the finding, dismissing Verigin’s claim completely and also Popoff’s counterclaim for another $3,000.

But the key part of the story is that it described Popoff as a “a Russian political refugee.” I’d never heard that before and thought it was a mistake.

A family story, however, did suggest Konstantine’s brother Michael wrote something negative about the czar and faced imprisonment for it. Authorities arrived to arrest him but he escaped to Canada with Konstantine’s help. Michael was in Canada by 1912 and they jointly purchased the property just south of Slocan City that became the Popoff farm.

I sent the item from the Sun to Jonathan Kalmakoff of the Doukhobor Genealogy Website, whose sleuthing quickly unearthed several astonishing items. While I knew from Konstantine’s World War I enlistment papers with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces that he’d previously spent 14 months in the Russian navy, I had no inkling of the events that took place during that time.

It turns out that as a petty officer in the Russian volunteer fleet, Konstantine was already known by the alias Popoff and helped lead the Baltic Sea mutiny — otherwise known as the Krondstadt uprising of July 1905.

Konstantine was imprisoned three times in Odessa for participating in strikes. At one point, 15,000 sailors were said to have demanded his release. Instead, in 1906 he was court-martialed and sentenced to be shot. According to the Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette of March 20, 1907:

Escape seemed hopeless, when the handsome sailor managed to interest the daughter of the jailor. A romance sprang up that ended in the girl’s stealing the keys of the prison and letting her lover go free. Popoff managed to escape into Italy. There he signed as a seaman on a ship board for America. Arriving here, got shore leave. Then he promptly deserted.

A somewhat conflicting account in the New York Sun the same day didn’t mention the part about romancing the jailer’s daughter. It just said the execution “was delayed for some reason” and one morning the jail-keeper rose to find Popoff gone.

Konstantine Popoff (far right) with his Russian navy unit, ca. 1905.

(Courtesy Nina and Thelda Rindler)

It added that Popoff joined the crew of the Russian steamship Gregory Morch, which left Odessa on Jan. 18, 1907 and arrived in New York on Feb. 20. Popoff supposedly appeared on the manifest under his real name, Konstantine Piroshko, listing himself as an able-bodied seaman. A few days after coming into port, Popoff came ashore.

Supposedly he had been in New York before and liked it. (Was this the trip Emilie referred to in her autobiography as occurring in January 1905? If so, there’s no record of their arrival.) He decided he would stay and got a job helping to build one of the East River Tunnels from 34th Street to Long Island City.

He looked up friends in the city and was soon welcomed by a branch of the Social Revolutionary body. According to the Sun:

He is a straightforward young fellow, not afraid to tell the truth.

“How did you get here?” someone asked him.

“I came ashore from the Gregory Morch,” said Popoff.

“But you went through Ellis Island, did you not?”

“Ellis Island?”

They told him that he would not be allowed to stay in America unless he had passed the entrance exam. Yet if he came forward, he might be at risk of being returned to Russia and shot. But at the first opportunity, he took the boat to Ellis Island.

Alternatively, the revolutionists committee in Russia wrote to American friends about Popoff and when he landed they were waiting for him. He was hidden for a few days, then given work. But the captain of the ship he had been on reported his desertion. Detectives soon located and arrested him.

In either case, he was detained. But Russia had not requested his deportation and he was not a criminal, although he was in the country contrary to law. Popoff’s friends hired a lawyer named Rosalsky — either Alexander or his brother Joseph, depending on conflicting accounts — to represent him before the board of examiners and make a case for him as a political refugee. At the hearing, the board threw up their hands. They didn’t know what to do either.

So Rosalksy wrote to Oscar Straus, the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, who in turn sent a directive to the commissioner on Ellis Island that Popoff should be freed — a “prompt and final decision” that won Straus the admiration of the Brooklyn Eagle, which praised “his broad, human sympathy, his fellow feeling for the oppressed of other lands.”

“I thank you gentlemen,” Popoff said as he left the island. “I am going to become an American as soon as I can.”

The Star-Gazette said Popoff also declared he would join the US navy. That night he celebrated with friends on 110th Street. Another party of friends waited in vain for him on East Broadway.

“Popoff got word that a battery of camera men were sitting up for him,” the Sun reported. “He had escaped the Russian bullets — he would not brave the snapshots. There might be complications arising.”

How much of this story was true? There were already discrepancies between the newspaper accounts. Was any of it invented to bolster his refugee claim? And where was Emilie in all of this? Was she the jailer’s daughter? Or was that someone else? Emilie’s parents were Theodor and Emilie Rangno. We don’t know what her father did for a living, but her mother and brothers later joined her in Canada.

On a 1944 border crossing document, Emilie indicated she arrived in New York in 1905 aboard the “Gregory Merchant.” Close enough to the Gregory Morch, although she was wrong about the date. If she was aboard that ship, she must have arrived in November 1906 or February 1907. Her autobiography indicates she came with Konstantine, although I suppose it’s conceivable they were on separate sailings and reunited in New York.

Then Jon Kalmakoff found an extremely interesting document (pictured below) which upended part of what I thought we had just learned.

It shows “Constantine” and “Annie” Popoff, a married couple from Nelson, crossing the border at Marcus, Wash. in January 1908, en route to Chicago to visit a brother-in-law named John Berg. Konstantine had two brothers and three sisters while Emilie had two brothers, but nowhere on the family tree does the name Berg appear.

We can be fairly sure this was our Konstantine Popoff, though. He was listed as 25, which matches his known birthdate, and his birthplace was Rostov, which also matches. He was a Russian citizen and listed his nearest relative as his father John of the Rostov region of Russia. (His parents were actually Jacob and Matrona Piroscho. Both later came to Canada, although Jacob — who, as seen earlier, accused Peter Verigin of assault — didn’t stay long.)

However, his profession was listed as printer — not an occupation Konstantine was ever known to have held. The document also states he had been in the US in 1906-07 at “different places,” before leaving the country in April 1907. So much for joining the American navy.

Popoff indicated his initial arrival at New York was aboard the Gregory Morch on Nov. 11, 1906, not February 1907 as reported in the New York Sun. The boat only made two round trips on that route. It departed Odessa on Oct. 27, 1906, passed through the Mediterranean, stopped in Greece and Sicily, and then continued to New York. It did indeed arrive on Nov. 11. The second departure was on Jan. 18, 1907.

Kalmakoff checked the manifest of the SS Gregory March, but Konstantine wasn’t listed — although as a crew member, perhaps he wouldn’t have been.

Was Annie really Emilie? The evidence suggests otherwise. Annie’s age was given as 24, four years older than Emilie would have been at the time. Her birthplace was also listed as Rostov, whereas Emilie was born in Odessa. And her nearest relative was identified as her father-in-law, whereas Emilie’s mother and siblings were alive.

But most importantly, we know Konstantine and Emilie married at Winnipeg on April 10, 1908. So either Konstantine was married before (and divorced early that year) or he and Annie were not actually married. If Annie was not Emilie, was she the jailer’s daughter? The above document states she arrived in New York on June 6, 1907 aboard the Kaiserin Augusta Victoria. In fact, the ship arrived three days later. But her name does not appear on the manifest, or at least she is not easily identified.

Konstantine had a sister named Anna, who is not known to have come to Canada. It seems unlikely, but perhaps this was actually her, despite being described as his wife.

In any event, it’s surprising Konstantine was already in Nelson as of January 1908, for I thought he and Emilie did not come to BC until after their wedding. They bought a ranch at Taghum and lived there until moving to the Slocan in 1912.

Aside from the 1917 newspaper reference during his court battle against Peter Verigin, Konstantine’s history as a revolutionary was never mentioned again.

Konstantine, Emilie, and daughter Vera Popoff, ca. 1909

(Slocan Valley Historical Society 2013-01-3093)

Although Konstantine’s brother Michael originally intended to settle in the Slocan, he and wife Marie soon moved to Vancouver. More about him turns up in those newly-digitized pages of The Vancouver Sun, including this item from Feb. 13, 1933.

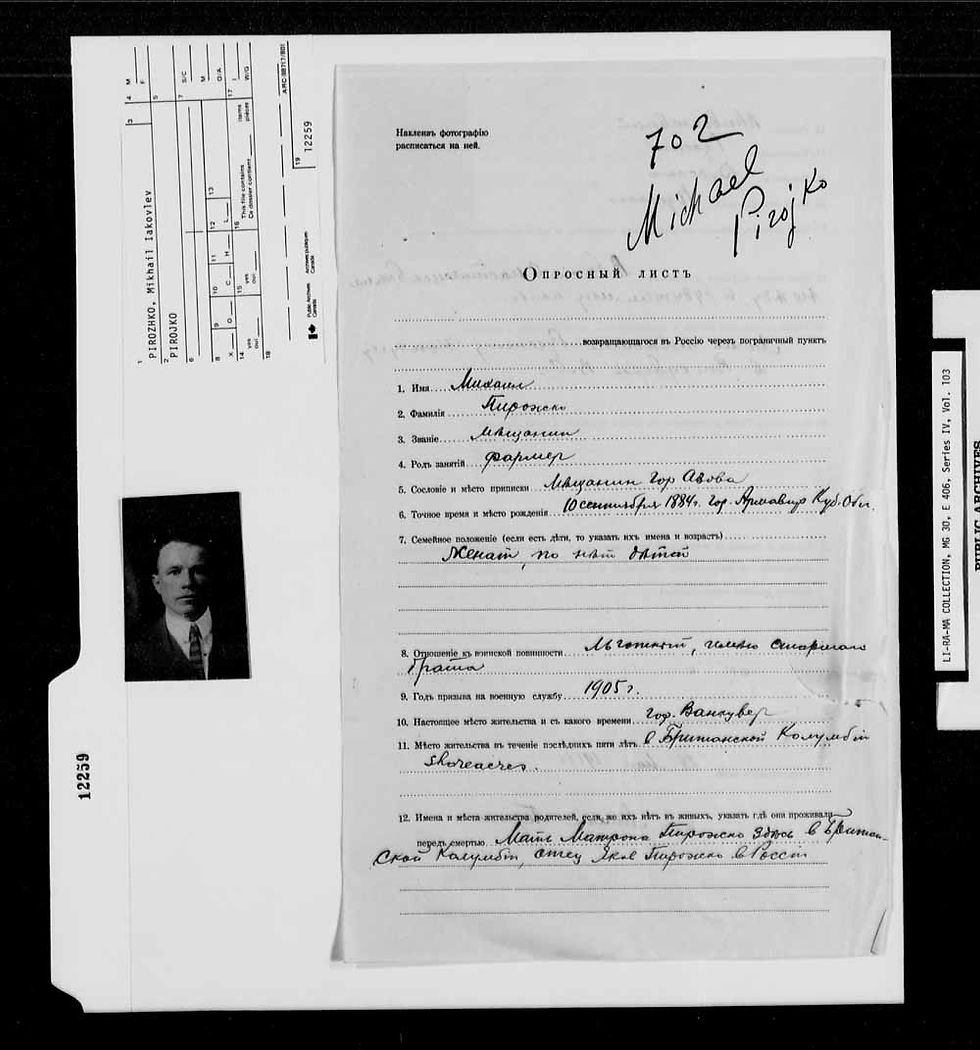

The National Archives has digitized his immigration file, which consists of a photo and two-page form written in Russian. (They also hold a file on Emilie, consisting of a letter she wrote in Russian to the Russian counsel at Vancouver in 1917, plus another letter whose date and intended recipient I can’t make out.)

Immigration file of Mikhail Iakovlev Pirozhko, aka Michael Pizojko.

By 1948, Michael was working as a grave digger and having marriage problems. His wife Marie, whom he wed in Nelson in 1916, was suing for divorce, “alleging her husband has threatened her, published scurrilous statements about her, has shamed her by suggesting that he is a Communist and has not supported her for a year.” The judge urged them to settle out of court.

Michael died in 1952, age 67. Marie long outlived him. She died in 1986, age 89.

Michael and John Piroscho, brothers of Konstantine Popoff, date unknown.

(Courtesy Nina and Thelda Rindler)

Comments